Statements of Service Performance Explained!

By Craig Fisher – Consultant, RSM

The aim of this article is to assit you to better understand the nature of and requirement for Statements of Service Performance (SSP) as part of your annual reporting.

Experience from early adopters and leading organisations is that achieving a common level of understanding early in the process is very beneficial as regards the success and ease to produce a compliant, relevant, and informative SSP, and to the overall quality of the outcome.

Why are these new standards required?

SSPs are now mandatory for all registered charities in New Zealand, albeit depending upon entity size there are varying effective dates. Smaller charities have already been providing SSPs for a couple of years now.

SSPs were developed to enhance the transparency of charities and to assist them more effectively communicate their activities and impact to stakeholders. For registered charities, key stakeholders include Charities Services (the regulator), IRD, potential funders, as well as the general public as part of the charity’s social licence to operate. The primary stakeholders of any entity are its owners, or in the case of a charity all those stakeholders with an interest in it including its beneficiaries, donors and other funders, potential donors and other funders, regulators such as Charities Services, IRD etc.

Annual financial statements have an important role in accountability and transparency to stakeholders. They show the assets and liabilities under the entity’s control at a point in time and the results of its operations (surplus or deficit) over a specified period, usually a year. Annual financial statements are also important to enable decision making over resource allocation by an entity’s governing body and management. For companies and other For-Profit organisations, financial statements are very useful for this purpose. This is due to profit generated and/or growth in net assets being a primary key performance indicator (kpi) or measure of success for shareholders or other owners.

However, the success of a charity is not easily measured by whether it made a surplus or a deficit. While a statement of financial performance is important hygiene information that can be a measure of activity, and sometimes financial efficiency, it does not help assess whether the charity is actually delivering on its purpose. (In fact, the easiest way for a charity to improve its financial surplus is to cut expenditure on delivering on its purpose!)

Sadly, many funders and other stakeholders have also in the past made support decisions based largely on the limited information contained within financial statements rather than a more holistic view of the entity. This has sometimes led to worthy, efficient and effective charities not being supported for such misguided reasoning as “they don’t look poor enough to need our support”.

The flow-on impact of this is that some charities have been overly influenced to structure their operations and accounting to show what they think will be the most desirable result to funders, often to look poor. When in fact this is usually detrimental to them operating with the most positive impact.

The development of service performance reporting was designed to provide a more appropriate measure of, and insight into a charity’s operations and effectiveness.

Hence, rather than just requiring charities to provide an annual financial report with details of their income and expenditure and assets and liabilities, they are now also required to provide key

information about the entity, why it exists, what it set out to achieve in a period, and what it actually achieved. This additional information is largely contained within the SSP.

What’s required?

The requirements for SSPs are expressed slightly differently for small and larger entities. However, the broad conceptual intent is the same.

Service performance reporting is based around two elements:

- Outcomes: what the entity is seeking to achieve in terms of its impact on society; and

- Outputs: the goods or services that the entity delivered during the year.

The Tier 3 accounting standard for NFP PBE entities requires the Statement of Service Performance to:

a) Describe the outcome(s) that the entity is seeking to achieve or influence through the delivery of its goods or services.

The outcomes are likely to be closely related to the mission/purpose reported in the entity information section of the performance report.

The main difference is that the mission/purpose is usually stated in broad or general terms and applies over the life of the entity. By contrast, the description of the outcomes in the statement of service performance should be more specific and focused on what the entity is seeking to achieve over the short to medium-term; and

b) Describe, and quantify to the extent practicable, the outputs (goods or services) the entity has delivered for the current year.

The standard for larger entities, PBE FRS 48, expresses the requirements in slightly more detail and contains more guidance. This makes sense in that larger charities are generally more complex and hence may need to consider more measures.

Of significant relevance is that both accounting standards are very principles based rather than prescriptive. This is in recognition of the fact that charities are unique as regards their purposes and

activities and hence should be allowed flexibility to choose what measures best allow them to communicate their impact.

However, for charities required to be audited, their SSP is also required to be part of that audit. The aim of the audit is to ensure the truth and fairness of the SSP disclosures.

PBE FRS 48 also notes the importance of considering qualitative characteristics which are attributes that make that information useful to users.

The qualitative characteristics to be considered in preparing an SSP and choosing what to include are:

- relevance,

- faithful representation,

- understandability,

- timeliness,

- comparability, and

- verifiability

When

SSP reporting is already mandatory for Tier 3 and Tier 4 entities i.e. smaller entities.

For larger entities (those with annual operating expenditure over $2m), the applicable accounting standard is PBE FRS 48 Service Performance Reporting. Due to the disruption caused by COVID19 the standard setter (the External Reporting Board or XRB) granted a deferral of the effective date of PBE FRS 48 until financial reporting periods beginning on or after 1 January 2022. However early adoption is permitted.

The experience of many early adopters has been that there is benefit in early adopting as it takes time to decide and refine what should be reported and how this should be presented. It is also important that the appropriate systems are in place to collect and collate the relevant information for SSP reporting. These can take time to implement. In addition, ideally all information in an annual financial statement should be presented along with comparative figures. This necessitates making selection decisions and ensuring accurate recording systems are in place and operating a year earlier than the mandatory reporting period.

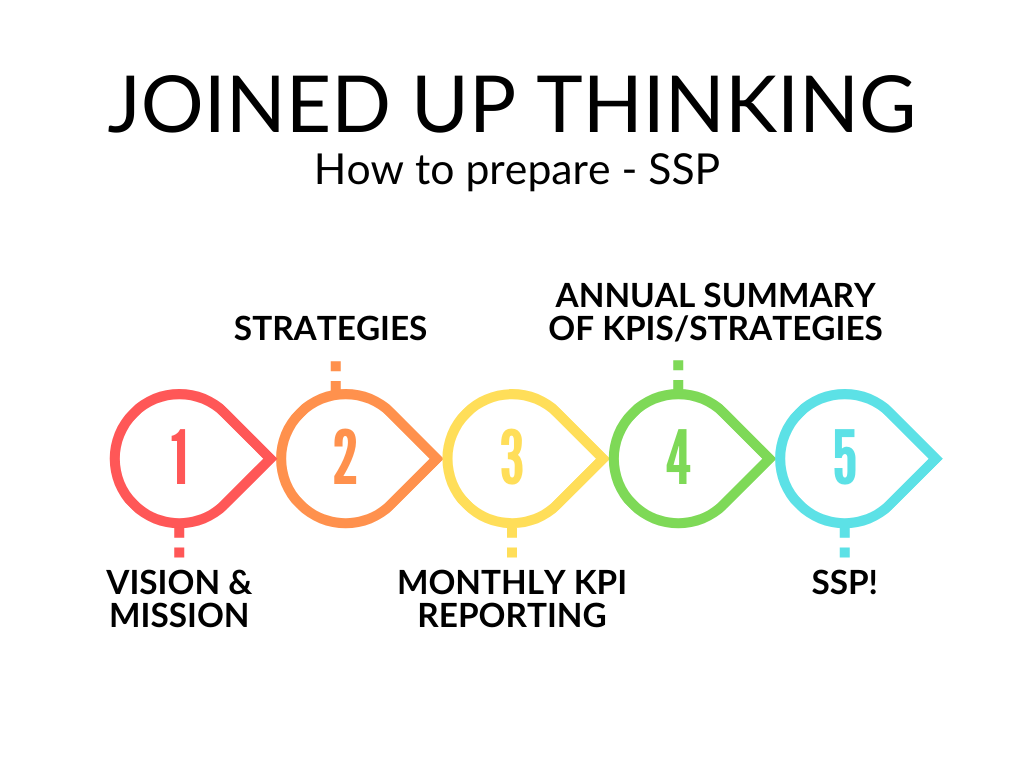

How to prepare a SSP – Joined up thinking

One of the keys to writing a great informative and useful statement of service performance is (SSP) being clear on why the organisation exists, what it is attempting to achieve, and the strategies it will adopt to achieve its aims.

The clearer the thinking and planning, the easier it is to report on.

Ideally in any organisation the governing body should be very clear on the organisation’s raison d’être; its reason for being. This is often encapsulated in a vision or mission statement. However, the practical work begins when the organisation then sets the specific strategies it will employ to achieve its aims.

These may be annual or multiyear and enduring in nature. Regular monitoring and reporting to the governing body ideally should be focused on these strategies.

Many organisations use a dashboard and KPIs (key performance indicators) in order to succinctly monitor and report their progress throughout the year. Then at the end of the year their summary reporting is largely just an aggregate of their KPIs.

Hence the “joined up thinking” comment in relation to a SSP is where the SSP is essentially a summary of the KPIs – the measures of the key strategies the organisation has employed to achieve its raison d’être. If you are clear on the big picture and the strategies employed, then generally creating a valuable and informative SSP should be relatively straight-forward.

For some charities there is a very direct linkage between their raison d’être and their impact being able to be expressed in measurable KPIs. For others it is more difficult to articulate and demonstrate their theory of change. SSPs are also often a mixture of quantitative and qualitative descriptive information. From the experience of leading early adopters of SSPs, the most successful development experiences have involved strong ownership and direction from the governing body but also active involvement at an early stage of a wide cross section of people from throughout the organisation.

A SSP is not just a governance responsibility, a management task, an accounting exercise, a communication and marketing opportunity, an operational team motivator – rather, done well, it should be all these things.

About the author:

Craig is a Consultant with RSM specialising in governance, strategy, audit and assurance advice, and with a strong interest in the sustainability of impactful organisations.

Craig is a recognised specialist in the not-for-profit and charitable sector, has a strong interest in good governance, and holds a range of governance roles. He is an independent Councillor of the Auckland District Law Society, independent Risk Assurance and Audit Committee Chair of Ngati Whatua Orakei, Chairman of the Fred Hollows Foundation New Zealand, and a trustee of the Sustainable Coastlines Charitable Trust. Craig is also a member of the Wise Trust Board.

Craig has a long history in standard setting including serving on the New Zealand Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (NZAuASB) from its inception until 30 June 2020. He has represented New Zealand internationally in assurance and ethical standard-setting matters.